If economics is to be a tool for moving human societies away from endemic crisis toward a resilient and thriving future, then its renewal starts with a new compass and map that are fit for our times.

As John Maynard Keynes wrote in 1938, “Economics is the science of thinking in terms of models joined to the art of choosing models which are relevant to the contemporary world.” It’s ironic that some of the most profoundly influential models still shaping economic thought today were created in Keynes’ own era. If he were alive this century—and were witness to the scale of social and ecological crises that we currently face—he would no doubt be urging his fellow economists to create new models that reflect the knowledge, reality, and values of our times. He would be right.

Last century, when postwar economic thought adopted growth as its de facto goal, GDP became the economist’s compass: it depicted progress as an exponential curve, measured with the single metric of monetary value in pursuit of endless increase, no matter how rich a nation already was. The impact of wealthy countries continuing to prioritize GDP growth over tackling inequality and protecting the living world is now all too clear.

This century, we need a far more ambitious and holistic goal: human flourishing on a thriving, living planet. And one compass that can guide us turns out to look like a doughnut (see Chart 1). It prioritizes the essential needs and rights of every person—from food, water, and health to decent work and gender equality. At the same time, it recognizes that the health of all life depends upon protecting Earth’s life-supporting systems: a stable climate, fertile soil, healthy oceans, and a protective ozone layer. In the simplest terms, the doughnut enables humanity to thrive between a social foundation and an ecological ceiling—in other words, meeting the needs of all people within the means of the living planet.

Embracing such a compass replaces the single GDP metric with a dashboard of diverse social and ecological metrics. It entails redefining success not as endless growth but rather as thriving in balance between social and ecological boundaries. This calls for a profound paradigm shift. Given that no economy in the world has met the needs of its entire people within the means of the living planet (Costa Rica is the closest to doing so), no economy should yet consider itself “developed.”

If the doughnut is a compass for 21st century progress, what kind of macroeconomic worldview would give humanity a chance of getting there? Back in the 1940s, when Paul Samuelson first drew the iconic circular flow diagram—depicting the monetary flows that circulate between households and firms, and banks and governments—he essentially defined the model of the macroeconomic that would come to dominate 20th century economic thinking. This model is still applied as a foundational conceptual map of economic systems today.

Yet, in the words of the systems thinker John Sterman, “The most important assumptions of a model are not in the equations, but what’s not in them; not in the documentation, but unstated; not in the variables on the computer screen, but in the blank spaces around them.” What is not seen in the blank spaces around Samuelson’s circular flow model are the vast quantities of energy, materials, and waste involved in economic activity. Leaving these invisible has proved profoundly dangerous for life on Earth.

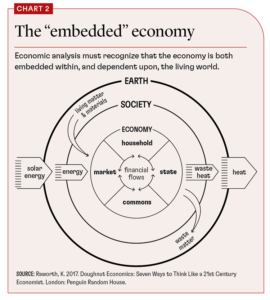

A 21st century map must provide a far more holistic and bio-centric starting point by recognizing that the economy is both embedded within, and dependent upon, the living world.

The seemingly obvious step of depicting the economy as a subsystem of Earth’s biosphere is also one of the most radical and essential acts for renewing economics this century. It calls on all economic analysis to recognize that the economy is an open system—with large inflows and outflows of both energy and matter—within our planet’s unique and delicately balanced biosphere.

From this perspective it becomes clear that energy, not money, is the fundamental currency of life, underpinning all human, ecological, and industrial systems. Energy dependence then lies at the heart of the economist’s understanding. We must recognize that humanity’s continual use of resources puts intense pressure on planetary boundaries, creating a high risk of undermining the ecological stability on which human and all life fundamentally depends.

When we situate the economy within the living world in this way, the 20th century pursuit of endless growth sits in sharp tension with empirical evidence to date. The ambition of decoupling consumption-based carbon emissions and material use from GDP growth in today’s high-income economies is not happening at anywhere near the speed and scale required to avert critical tipping points.

This compels us to question the limits to growth and explore postgrowth economic possibilities, particularly in wealthy economies. Facing up to the ecological consequences of economic activity is now a critical moral obligation.

A new compass for economic thought also entails taking a more holistic view of the range of economic activity that provides for people’s essential needs and wants. Mainstream economic thought has been dominated for over a century by an ideological boxing match over the respective roles of the market and the state. Both sides have lost sight of two other critical sources of provisioning: the household and the commons. Much of the value they generate is not reflected in GDP, but they are a key part of the embedded economy model because the value they produce is critical for human well-being.

Take, for example, the unpaid caregiving done predominantly by women in the home, which is essential to well-being and systematically subsidizes paid work. Similarly, the commons can be a highly effective means of provisioning goods and services whose value is not reflected in monetary exchange—from open-source software to Wikipedia to transnational watershed management.

Economic renewal must begin with the goal of human flourishing on a thriving, living planet. If we hope to get there we need macroeconomic models that recognize the economy as a subsystem of the living world. Within it, finance must be redesigned to be in service to the real economy, in service to life. This constitutes a conceptual revolution, and it is essential.